When it comes to agriculture, weather can be your best friend or your worst nightmare. The difference between a good crop year and a bad one seems to boil down to the timing of the most adverse weather rather than the weather extreme itself.

In 2020, corn and soybean production already have fought off two familiar foes that in other years would have destroyed production potential, but so far the early spring flooding and recent hard freezes in the Midwest and neighboring production areas has not had the big negative impact on potential crop development that last year’s wet and cool weather had.

Early spring flooding was widespread in the Ohio River Basin, lower Missouri River Basin and Mississippi River Basin. Flooding also occurred on the Red River of the North and along the Illinois River. However, unlike last year, the flooding and excessive rain seemed to shut off at just the right time to prevent a disaster in notable delays in farming activity.

The planting progress that has been seen so far this spring has been nothing short of amazing and reflects the determination of most farmers to not be shut down by Mother Nature for a second year in a row.

Some of the late winter and early spring flooding this year was worse than or at least comparable to that of last year, but only for a brief period of time. Notable planting delays occurred in the Delta, Tennessee River Basin and a part of the southeastern states. Planting continues behind in many of those regions as of mid-May, but producers in the Midwest were out planting their fields this year faster than usual despite frequent bouts of rain and wet field conditions. Every opportunity was taken to get into the fields, and this strategic plan has paid off well with field progress well ahead of schedule north of the Ohio River Valley.

Several weather forecasters cringed when it was learned that planting for corn and soybeans had advanced so amazingly fast in early May. Minnesota had 76% of its corn planted as of May 3, and Iowa was 78% done. At that time, frost and freezes are expected around mid-month, and it was feared that damage would come to early emerged corn at that time, but the concern was only for the upper Midwest. Then it was learned that soybean planting had reached 46% complete in Iowa on May 3 — the fastest planting pace on record since 1974. Minnesota had 35% of its crop in the ground as well, and some of the early crop was beginning to emerge when the bottom fell out of the temperature forecasts.

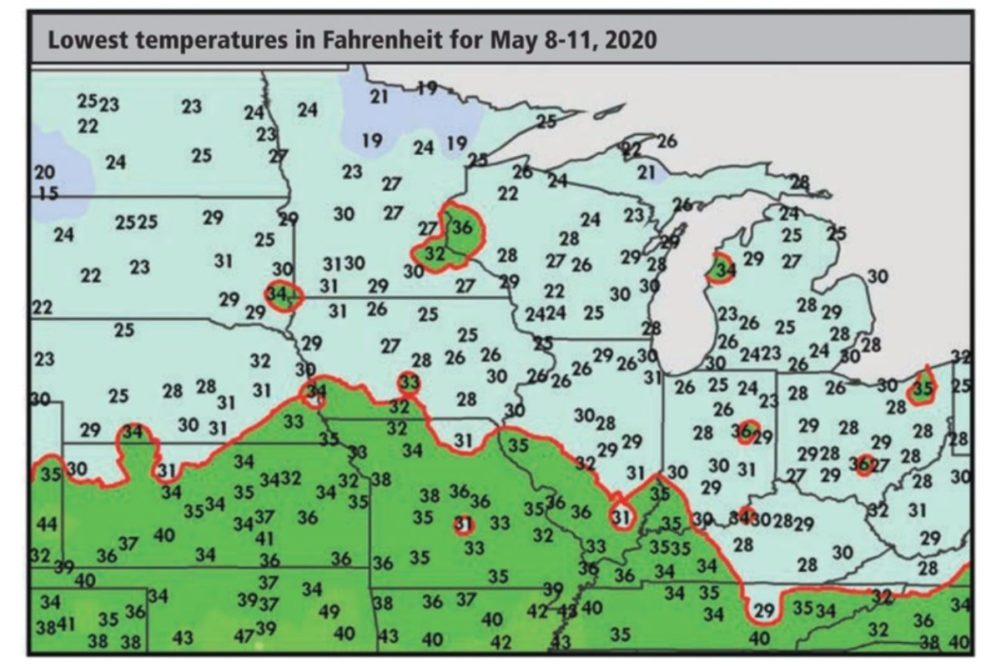

Cold weather that was supposed to have been limited to the upper Midwest and northeastern Plains around mid-May turned out to be much more intense and extended farther to the south. Freezes May 8-10 occurred as far south as northern Kansas, central and southeastern Iowa, central Illinois, northwestern Kentucky and North Carolina. The cold was notably more intense than originally anticipated with extreme low temperatures falling to the teens in central North Dakota and southwestern Wisconsin while hard freezes (23° to 28° Fahrenheit) occurred southward into much of northern Illinois, northern and eastern Indiana, parts of Kentucky and portions of Ohio. No one expected it to be that cold that far south — at least not a week before the occurrence.

Corn and soybeans had emerged on a portion of each Midwestern state’s cropland by May 8 and it was feared the early emerged crops were doomed. However, in retrospect, the cold could not have occurred at a better time.

The growing point of corn was still below the surface of the soil and most crops had not developed quite enough to be permanently harmed by the cold. Low futures market prices and a faltering world economy left many farmers with little incentive to replant corn, but a small percentage of corn and soybeans may ultimately get replanted. However, the overall damage that resulted from the May 8-10 freeze event did not rock the marketplace very much, and the potential huge crop of corn and soybeans projected for the nation in 2020 may still be intact.

Assessments of the damage were still underway at the time of this writing, but it is a miracle that crops were not more seriously impacted by the freezes. It was just as remarkable that spring flooding did not continue longer than noted. As a result of all of this, the US corn crop is still poised to be very large and soybeans likely will still perform well with some of the more damaged crops likely to be replanted in sufficient time to head off a production shortfall. That, of course, is not all good news. The large US crop and big production year in South America this year will keep market prices down as will the global economic crisis.

In the meantime, India has had a beautiful winter crop of grain and oilseeds and China is poised for big crops this year. Australia likely will see a much bigger winter wheat, barley and canola crop. There is still room for trouble, and parts of Europe and the Black Sea region certainly have attained a great deal of early spring market attention because of lingering dryness from 2019. These areas will be monitored closely for production cuts later this spring and summer if the weather trends too warm and dry.

Back in the United States, one of the larger casualties to the May 8-10 frost and freezes may have been to Indiana soft wheat production. The crop was in the boot to heading stage when low temperatures fell to the range of 23° to 26° Fahrenheit, which may lead to some production cut just as similar low temperatures did in southwestern Kansas, western Oklahoma and parts of western Texas in the late April freeze. With all that noted, Indiana is not a huge wheat producer, but perhaps with its losses and those noted in parts of hard red winter wheat country there might be some dent in US small grain production.

The prospects for spring wheat in the northern US Plains and Canada this growing season are looking very good with moisture abundance expected. The biggest threat to crops in these areas might be for a wet harvest.

The bottom line to all of this is that despite some amazing record and near-record cold weather from Canada to the Midwest and northern half of the US Plains there has not been nearly as much damage as feared. US crops have now escaped yield losses because of late planting (resulting from wet conditions) and now missed out on what could have been a more serious freeze event if the cold had occurred just one or two weeks later. Despite all of the fear, US crops are still on the road to success, and without a La Niña event or negative Pacific Decadal Oscillation this summer there may not be much to fear. Production could still be high. Some dryness is expected to stress summer crops, but the impact may not be so bad depending on how much subsoil moisture remains when the rains finally shut off.