KANSAS CITY —

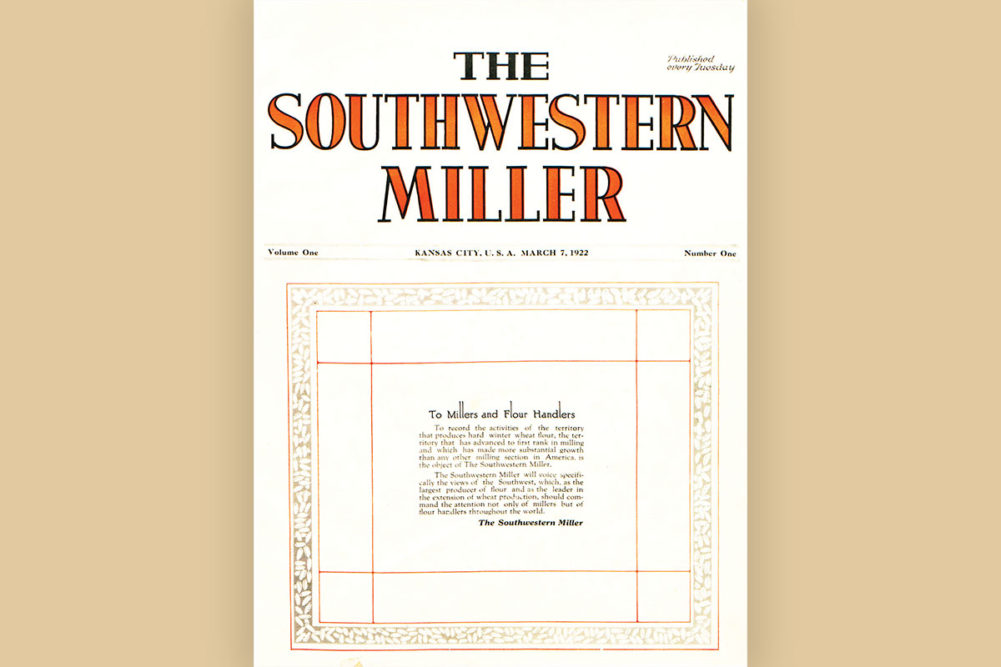

The next issue of Milling & Baking News, to be published March 8, will mark the 100th birthday of this publication and will include a special feature chronicling its history. The approach of that proud anniversary in a fortnight offers an opportunity for reflection about the happenings in the milling and the broader world in 1922 and how it shaped the industry since. Many of the stories published in the first handful of issues of The Southwestern Miller (as the publication was known until 1972) demonstrate the unique dynamics of the time, helping explain what would draw three young brothers — David Sosland, Sam Sosland and Sanders Sosland — into the then crowded field of milling journals.

KANSAS CITY —

The next issue of Milling & Baking News, to be published March 8, will mark the 100th birthday of this publication and will include a special feature chronicling its history. The approach of that proud anniversary in a fortnight offers an opportunity for reflection about the happenings in the milling and the broader world in 1922 and how it shaped the industry since. Many of the stories published in the first handful of issues of The Southwestern Miller (as the publication was known until 1972) demonstrate the unique dynamics of the time, helping explain what would draw three young brothers — David Sosland, Sam Sosland and Sanders Sosland — into the then crowded field of milling journals.

The ostensible reason for the creation of The Southwestern Miller was to level the playing field for millers of the hard winter states. Southwestern millers were seeking to compete for sales to commercial bread bakers with millers from the spring wheat states, which had been dominant until then. Reliant on a slowly fading family flour business, millers in the Southwest seemed disadvantaged versus the well ensconced mills of the Northwest. Still, signs were abruptly emerging in March 1922 pointing to a promising future for the hard winter states, to a blurring of the lines separating the different milling regions of the country and to impending changes in grain-based foods.

This blurring surfaced in the very first issue, in a story describing the problems of a new mill — Liberty Milling Co. in Kansas City. When the company was unable to cover its debts to equipment suppliers, ownership was transferred to “Minneapolis interests” — Washburn Crosby Co. (six years before it was renamed General Mills, Inc.). The company’s first mill in the Southwest, it was located on the site where General Mills’ largest US flour mill operates today. Washburn Crosby’s foray into the Southwest was not an isolated event. A month later, another prominent Minneapolis miller A.C. Loring, president of The Pillsbury Flour Mills Co., was in Kansas City, negotiating purchase of the Atchison Mills in nearby Atchison, Kan.

More telling than the investments in the Southwest by the leading millers of the Northwest was success hard winter millers were enjoying selling flour into Central states markets. Mills in states like Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and Pennsylvania were reportedly purchasing hard winter flour from the Southwest and packing it under their own brands. “These mills have become the largest distributors of Southwestern flour,” an article read. So alarming was the success of the southwestern mills in the region, the state government of Ohio instituted a policy that no flour would be purchased for its various institutions unless it was milled in the Buckeye State.

Hints of impending industry changes may be found in the obituary of William G. Crocker, who died April 17,1922, at the age of 58. While often referred to in histories as a “beloved director” of Washburn Crosby, Mr. Crocker had served since the 1890s as the head of the company’s millfeed department, a role he maintained his entire career. He grew ill in 1920, and a year before his death, Washburn Crosby honored Mr. Crocker by using his surname for responses to consumer inquiries. The company chose the name “Betty” as a “friendly sounding name.” (Mr. Crocker’s widow was named Mary.)

Finally, a March story offered the view of an observer in Rome that Russia would not be able to resume its role as a large wheat exporter for at least three years. The estimate was wildly low. Russia at the time was in the midst of a famine, and the story portended food shortages in the years ahead culminating in the Russian Wheat Deal in the 1970s that would bring fame to this publication’s longtime editor Morton I. Sosland, who broke the story.

One hundred years later, the vigor of the grain-based foods industry has not ebbed. Neither has our excitement to share developments about what we are confident will be a dynamic, even thrilling future.