FRANKENMUTH, MICH. — It was in the late 1970s that Star of the West Milling Co. emerged from its longtime status as a small Michigan mill to grow through a series of acquisitions into a major regional milling company. During the last 10 years, the company embarked on its next phase of growth with a modernization effort that included the construction of two large flour mills, an ambitious sustainability program and continued diversification into non-milling businesses, including agronomy.

At the time of its centennial in 1970, Frankenmuth, Mich.-based Star of the West operated a single mill with 2,500 cwts of daily capacity. The company expanded in the late 20th century by acquiring a Michigan Farm Bureau mill in Quincy, Mich., in 1979; the Lyon and Greenleaf mill in Ligonier, Ind., in 1987; the Williams Brothers flour mill in Kent, Ohio, in 1999; and the Agway flour mill in Churchville, NY, in 2000. According to the 2001 Grain & Milling Annual, Star of the West’s milling capacity after the Agway deal was 20,000 cwts of daily milling capacity, making the company the nation’s 17th largest flour miller.

More recently, the company replaced its Kent mill with a new, larger mill in Willard, Ohio, and began work to replace its Ligonier mill with the larger facility located on the property where the existing mill operates. Today, before the Indiana project has been completed, Star of the West has 33,060 cwts of daily capacity, making it the 11th largest US milling company.

In a recent interview at the company’s Frankenmuth headquarters, Mike Fassezke, president of Star of the West’s milling business, said the investments in new mills were needed to demonstrate an unshakeable commitment to milling.

“We are in it for the long haul and investing in the company’s future, which of course is our customers’ future,” he said. “We’re looking to be a player long term in the milling industry. It’s really hard to spend the money it takes to build a 20,000-bag-a-day flour mill. And if you’re a company that is looking at quarterly returns, you’re never going to build a new flour mill. It just doesn’t make sense. We’re investing not for next year or the year after; we’re investing for the next decades.”

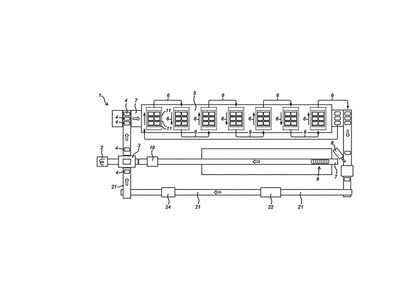

The company’s latest such investment is in the construction of a flour mill to replace its aging facility in Ligonier. The mill will have a total of 20,000 cwts of daily flour milling capacity, spread across three milling units.

With the company’s history dating back 153 years, many families have had employees at Star of the West over multiple generations, including Mr. Fassezke’s. His grandfather worked in a company feed mill, and his uncle was a truck driver for the business.

“I’d worked here during the summers, and I was finishing my last year of college when Dick (Krafft) called me and offered me a position,” he said.

“I actually turned down the offer, but after a couple more months of college, had a change of heart,” he said. “Thankfully, the position was still available.”

He began work with Star of the West in May 1981. A graduate of Alma College in Alma, Mich., with a degree in psychology and business, Mr. Fassezke eventually did go to graduate school — to the University of Michigan, for a master’s in business administration.

Richard G. Krafft Jr., who recruited Mr. Fassezke, was the longtime president of Star of the West and a prominent figure in the US flour milling industry. He was chairman of the Millers’ National Federation (now the North American Millers’ Association) in the mid-1980s. It was Mr. Krafft, who died in 2020 at the age of 90, who initiated Star of the West’s move in milling beyond Frankenmuth.

“When I got here in ’81, we had just purchased the Quincy, Mich., flour mill,” Mr. Fassezke said. “Before that Frankenmuth was our only mill. It was a 2,000-to-2,400-bag a day flour mill, and Dick sold all the flour himself. He sold every bag.”

Quincy is 13 miles north of the Indiana state line, just east of the town of Coldwater, 150 miles southwest of Frankenmuth.

While Star of the West’s only flour mill before Quincy was in Frankenmuth, the company owned grain elevators in nearby Gera and Richville, Mich., as well as feed mills in Frankenmuth and Richville. Michigan is a large producer of dry beans, and Star of the West had been processing beans at all three of the locations.

The company’s expansion in the late 1900s was not limited to flour milling.

“At the same time, we were also expanding our dry bean business,” Mr. Fassezke said. “We were expanding our elevator business. We got into agronomy, probably in the mid-80s. We already sold a little fertilizer here and there and some seed and stuff through our feed mill operations. But we really went all in in the mid-80s into our agronomy business. Today we have more than 30 agronomists on staff operating out of five locations within the state of Michigan. I think we’re the 36th largest provider of fertilizer, plant food, chemistry, seed, scouting consultation in the nation — everything an agronomy service company would provide. “

A business with a distinctive ownership, Star of the West was owned for most of its history by members of the Frankenmuth community. As the generations have passed, more and more shareholders now live all around the country. A total of 450 different individuals own stock in Star of the West.

Sales, both in dollars and units have grown dramatically over the past 40 years. Milling now accounts for just over half of the company’s annual sales.

The decision to expand and update the company’s Ligonier mill was inspired by an investment in 2014 to replace a small mill the company operated in Kent, in eastern Ohio, with a larger one in Willard, 80 miles to the west.

“We were landlocked right next to Kent State University, and it was a relatively small mill,” Mr. Fassezke said. “It was an old mill and had no wheat storage. We moved west to Willard, Ohio, to position ourselves near our largest customer and also where the majority of our wheat is originated.”

Willard represented the first greenfield mill for Star of the West, and a project of that magnitude initially made Mr. Fassezke and his colleagues nervous, he said. Ultimately, after almost 10 years of on-and-off negotiations with the customer, the mill was built and opened in 2016. The project entailed Star of the West purchasing about 15 acres in Willard. Flour is piped pneumatically to the bakery adjacent to the mill. Mr. Fassezke said the mill has the capacity to meet the customer’s needs and still ship a significant percentage of its outturn to other customers.

“It took a long time, but it worked out beautifully,” Mr. Fassezke said of the Willard mill. “It was a watershed moment for our company.”

In addition to achieving financial results the company had projected during the planning stages, the Willard mill gave Star of the West a taste of how milling technology had changed.

“We are tracking well ahead of our original financial plan, but there are all the other benefits of having a brand new flour mill —sanitation, food safety, automation,” Mr. Fassezke said.

Beyond Willard’s success, the Ligonier expansion was prompted by rising demand from longtime customers, Mr. Fassezke said.

“We have customers who are concerned with our ability to keep up with their growth,” he said. “One of the reasons we’re building Ligonier is because we have a couple of major customers that are adding plant capacity, and right now we’re running probably 6½ to 6¾ days a week on average for all five mills. We don’t really have a lot more to sell, so they’re concerned. And so we’ve addressed their concerns through a strategic plan that adds capacity.”

For the Ligonier plant, Star of the West has engaged Todd & Sargent, Ames, Iowa, as general contractor and Bühler, Inc., for the plant’s milling and cleaning equipment. Kice Industries, Inc., Park City, Kan., will provide the plant’s automation.

The new facility will consist of three milling units, one of which will be a standard soft wheat mill with 10,000 cwts of daily milling capacity. A second unit, with 5,000 cwts of milling capacity, will have the capability of swinging between soft wheat and hard wheat. It will be Star of the West’s first hard wheat mill, and Mr. Fassezke said the company isn’t certain it will end up milling hard wheat.

“I don’t anticipate us being a hard wheat miller, but at the same time, it will be flowed as a swing mill in case we would like to mill hard wheat,” he said. “Our interest in hard wheat would be in our soft and hard wheat blends. There are certain customers who would like to see some blends, would like a little higher protein in their soft wheat or a little lower protein in their hard wheat. We’ll be able to do that if we choose.”

Potential end-product applications he cited for such blends include biscuits (“they need a little more strength sometimes”) and refrigerated/frozen dough for home bakers who “need a little extra forgiveness in their flour,” he said.

A third unit, with 5,000 cwts of daily milling capacity, will produce only pathogen-mitigated flour.

Once the new facility is operational, Star of the West will decommission the original mill, which dates back to 1860.

Of the pathogen mitigation unit, Mr. Fassezke said the system is the first of its kind in the United States to be incorporated in a wheat flour mill, but the technology is being utilized in nearly 300 installations around the world. Most of the applications are non-wheat — nuts, oats and other grains, he said.

“A lot of these units have found their way to the Pacific Rim for a variety of different grains and food processes,” he said.

While Star of the West and other milling companies are riding high with demand straining the millers’ ability to keep up, Mr. Fassezke said he and his colleagues are positioning the business for the future, a time when the macro-milling environment may not be as positive, a time when older flour mills may not be able to meet customer requirements for efficiency, sanitation or sustainability.

“We are investing in our business,” he said. “We are in that transition period where we’re setting ourselves up to be a survivor in the milling industry. We’re going to be a player in the future and you’re not going to be a player with flour mills that were built in 1860, 1870, or 1880.”